Exit Music

Publication month has been and gone, and I've been busy

Hi all,

This is my very, very belated publication week newsletter, because publication week was (*counts weeks in calendar*), er, seven weeks ago. It’s not even publication month any more. In my defence, not only did I publish a book, I also started a new job. In a surprising career twist, I now work part-time in publishing — I’m the new classical music editor-at-large (glorious job title, don’t ask what’s large about it) at Faber & Faber. And what this means in practice is that, much to my own publisher’s chagrin, I’m possibly the first debut author ever to have direct access to her week-on-week sales figures. (My editor: ‘I mean. I wouldn’t recommend it. Maybe just don’t look?’).

On the mortifying topic of sales figures, if you do happen to read WTML, it would genuinely be a disproportionally big help if you felt able to leave a review or star rating on Amazon, Goodreads, Waterstones etc. You don’t have to have bought the book on these platforms to leave a review — I’d be thrilled if you got it out of the library or borrowed a copy from a friend. It helps people to know what they’re getting as well as massaging the anaemic algorithm. (The lovely reviews I’ve had so far have been beautiful and overwhelming.)

Alongside learning to work in a brand-new industry, I’ve written a piece for the Guardian on music and wellness, been on Radio 4’s Woman’s Hour, chatted gateways to classical music on ABC Radio Melbourne (where I also had to spontaneously come up with my favourite bridge — hands down the Clifton Suspension Bridge, the highlight of J’s revision for the otherwise godawful Life in the UK Test), and did truly lovely event with the playwright Naomi Westerman, author of The Happy Death Club, at Daunt Books in Hampstead. Phew.

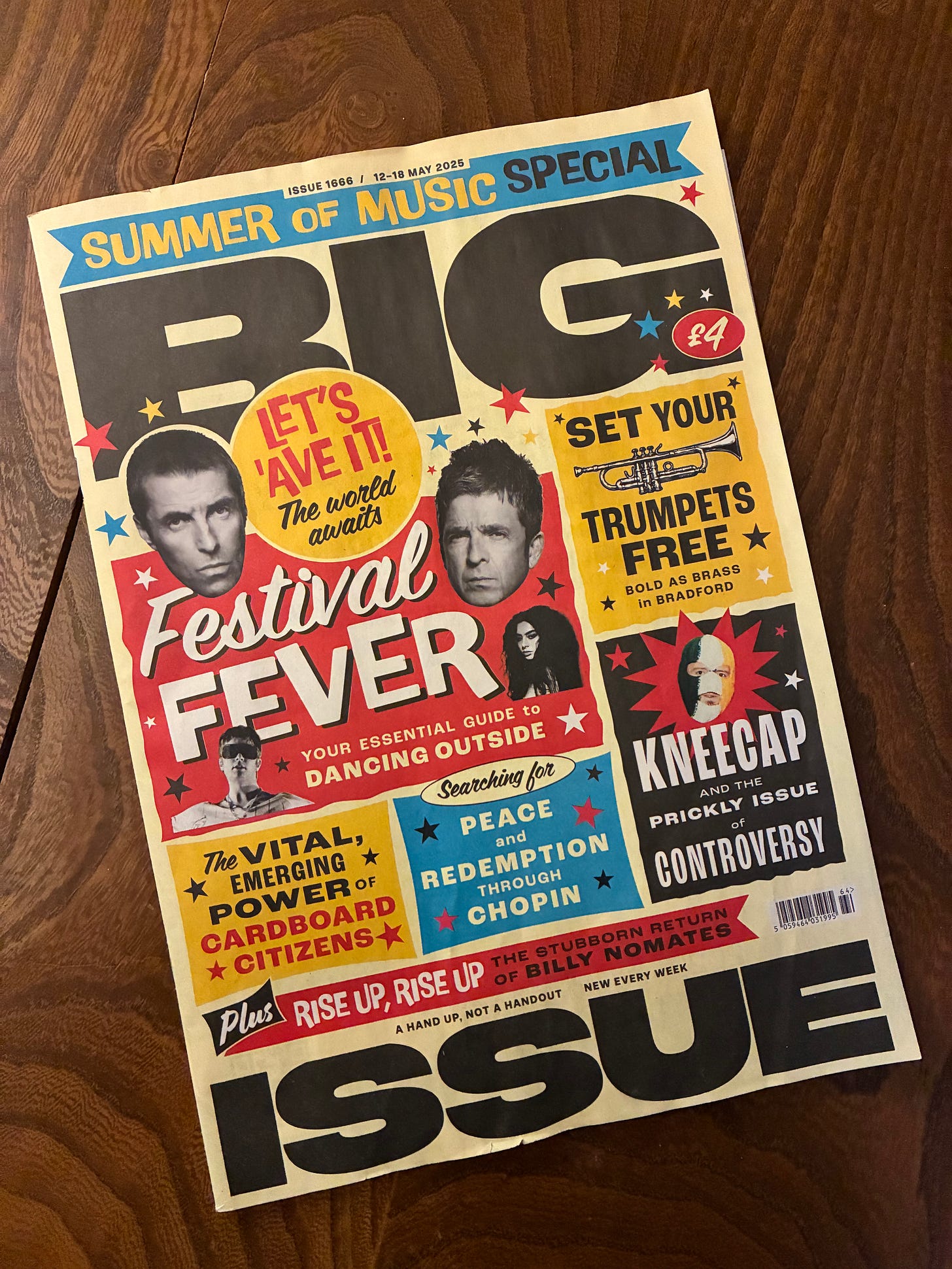

Mostly, thought, I’m writing as an excuse to send you a piece I loved writing for the Big Issue, which came out in the print edition this week, and for which they commissioned the gorgeous illustration below from Giovanni Simoncelli. In something of a coincidence, the issue also contains a brilliant article by Jess Lardner — we took the same bus to school, and our mums are in the same book club — about the independent music festival she’s set up in Somerset, called Homestead. An exciting week for a tiny Dorset village.

Exit Music

It was all the music’s fault.

A gallingly beautiful April morning. The day after my dad, out of the blue, had died. He was 68; I was 31. On the drive back from the hospital – where my mum, my brother and I had arrived to find that he wasn’t so much dying as already dead – I’d stared into the car footwell and tried on this new reality for the first time. Gone. Pancreatitis, a disease I’d never heard of. Dad will never meet my partner, see how my life turns out.

My dad was a classical and jazz guitarist. The guitar’s sound had been the wallpaper to my childhood: cascading classical arpeggios, noodling over jazz chord sequences he’d recorded onto blank cassettes. That morning, its absence was another emptiness blanketing the air of our home.

And now, something unlistenable was seeping from my mum’s laptop. An awful, sickening semblance of him. Music my dad had played, and it was about to tip me over the edge, and I was suspended, weightless in this place where grief curdled in my abdomen. I was holding it together, but music does this thing where it makes you lose it and cry, and I didn’t want that. I didn’t want to dissolve so soon.

I insisted we turn it off.

The gravity holding me in the world I knew had stopped working. A force I hadn’t known was there.

It was the rage that surprised me most about grief. Most of all, I was angry with music. This was far from ideal, given that I was a musicologist: music was what my life was made of. As a teenager, I would have done anything for a life in music. First I’d trained as a classical trombonist, and then I’d taken the academic route, ultimately teaching and researching music in universities. But after my father died, I couldn’t listen to it. Instead, I sought out podcasts, chatter, television, distraction. Thrillers, explosions.

Days were spent motionless on the sofa disorienting myself within the Netflix labyrinth. It helped me forget who I was and what had happened, just for a while. Like the craft beer I drank.

In truth, though, I’d fallen out of love with music before my dad died. I’d lost touch with music behind a sandstorm haze of academic theories, and the perceived need to like or say the right things to stay in the academic in-crowd.

My scatter-gun grief-rage was looking for objects, and directed itself at rule-following and institutions. That summer, I went to a Proms concert at the Royal Albert Hall. A Mozart piano concerto, fleeting tones skipping up and down into the vast emptiness above us, and nothing could have seemed more pointless. The grand stupor of the audience, the way they all seemed to be dressed up nicely, obeying the bourgeois norms of the concert hall. What if I stood up? What if I shouted profanities?

It was a long time before I was able to come back to music. Music opens you up in ways you might not yet be ready for. Scrapes away at the strata of your grieving brain, the parts of you that aren’t yet ready to look at what’s happened.

What it took was braving the music my dad played and loved, and realising that anger didn’t need to define me. Realising I was holding on to the ability of certain music—John Coltrane, or Miles Davis, or Isaac Albéniz—to conjure the presence of my dad. I was afraid if I used it up, I’d lose him again.

But I didn’t need to hold on so tight, or to hide my vulnerabilities. What it took was remembering that music, when you get right down to it, is about play.

One day, about three years after he died, I made a choice and sat down at the piano. I rifled through a stack of music, and I found a Chopin prelude that looked straightforward. I’ve never been much of a pianist, which meant I’d never staked my identity on being good at the piano, never feared the consequences of getting things wrong. In some ways, it was a fresh start. My puppy accompanied me on her squeaky bear. Squeaky, squeaky, she contributed, as I bashed through a version of the prelude that would have left Chopin totally appalled. It was fun, remembering the familiar shapes with my hands, the cold, smooth weight of the keys under my fingers, the scent of the paper, the print of the notes. The pure wonder of how music is both rooted in this mechanical action, and somehow also elsewhere, intangible and deeply affecting.

My relationship with music will always be a work in progress. Much as we might want to, we never reach a final cadence in our relationships. Not even when we lose people. I’ve learned that to rekindle how I once felt about music, I needed to let myself forget the rules—and fall. And in this new reality where there is nothing holding me down, I hope one day I will learn to fly.

PS: If you’ll be in Oxford on bank holiday Monday 26 May, I’m doing an event at Blackwell’s bookshop in conversation with the incoming Heather Professor and author of Beethoven: A Life in Nine Pieces Laura Tunbridge from 5:30-6:30, and I’d love to see you there.

PPS: What’s that? Yes! Of course you can still buy While the Music Lasts to gift to your friends and enemies alike.

Love, Emily x

You write so beautifully and honestly - thank you Emily. We are focusing on the subject of Loss & Transition this month at The Informed Perspective and so this ties in nicely. What resonates with me is that feeling of anger even rage at the loss of someone dear to you. It’s so important just to recognise that loss affects us in so many ways and whatever you feel, it’s absolutely ok to feel this and to live this out. I write about this in our latest article- take a peep!